The Magi from the East: Nabataean Kingship, Herodian Fear, and the First Gentile Homage to Christ

The account of the Magi in Matthew 2 is among the most familiar episodes of the Nativity, yet it is also one of the most misunderstood. Tradition has transformed the Magi into distant, vaguely Persian mystics, detached from the political and economic realities of the first-century Near East. A closer reading of Matthew, set against the historical context of Judea and its eastern neighbors, suggests a far more grounded—and more unsettling—picture.

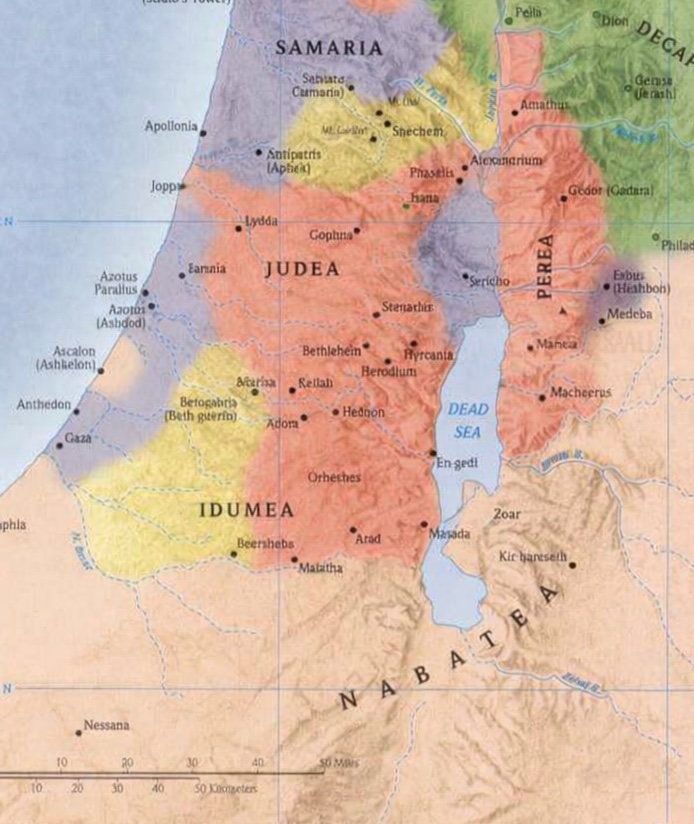

The Magi who came to Jerusalem seeking the newborn “King of the Jews” are best understood not as emissaries from a distant empire, but as Nabataean elites: men shaped by Arabian trade networks, regional politics, and long-standing entanglements with Idumea and the Herodian house. This identification not only clarifies the nature of their journey and gifts, but also explains the extraordinary fear their inquiry provoked in Herod and all Jerusalem with him.

Nabataea, Edom, and the Shadow of Seir

By the late first century BC, the Nabataean kingdom had emerged as the dominant power in Arabia and the Transjordan. Originally an Arabic nomadic people, the Nabataeans had displaced the Idumeans (Edomites) from their ancient stronghold in Mount Seir generations earlier, forcing them westward into southern Judea. This displacement set in motion a chain of historical consequences that would culminate in the reign of Herod the Great.

Under the Hasmonean rulers, the Idumeans were forcibly converted to Judaism and incorporated into the Judean state. Herod’s family rose to prominence within this context. Though nominally Jewish, Herod’s lineage remained suspect in the eyes of many: he was neither a son of David nor a native Judean, but the son of an Idumean father and Nabataean mother whose claim to kingship rested on Roman favor rather than covenantal legitimacy.

The Nabataeans, by contrast, had never been absorbed into Judea. They remained independent, powerful, and keenly aware of the region’s political genealogy. Their historical role in displacing Edom meant that they embodied, for Herod, both a reminder of his origins and a threat to his fragile legitimacy. Any Nabataean interest in Judean kingship would have carried an unmistakable subtext.

A Kingdom of Trade, Wisdom, and Authority

At the time traditionally associated with Jesus’ birth, the Nabataean kingdom was ruled by Obodas III, during a period of economic strength and diplomatic stability. Far from being a loose tribal confederation, Nabataea was a centralized monarchy with a royal court, priestly officials, and an educated elite fluent in Aramaic and Greek. Its power rested not on territorial conquest but on control of the most lucrative trade routes in the Near East.

Nabataean caravans moved frankincense and myrrh from southern Arabia to Gaza and the Mediterranean world. These commodities were rare, costly, and politically significant—compact forms of wealth suitable for royal tribute and diplomatic exchange. The Nabataeans were not merely merchants; they were gatekeepers of luxury, mediators between east and west, and interpreters of signs in a world where religion, politics, and astronomy were inseparable.

Within such a culture, it is entirely plausible that learned court officials—men Matthew calls magi—would study celestial phenomena, interpret them as divine communication, and act upon them with deliberation rather than haste. The discovery of the Nabataean zodiac at Petra testifies to a sophisticated tradition of astral symbolism and observation in the broader Near Eastern world, reinforcing the likelihood that such figures were trained to read the heavens as a meaningful, intelligible text rather than a source of sudden omens.

“From the East”: Direction, Not Distance

Matthew describes these men as coming “from the east,” a phrase often assumed to imply Persia or Mesopotamia. Yet in Second Temple Jewish usage, “the east” was a broad, relational term defined from the standpoint of Judea. It encompassed Arabia, Edom, Nabataea, and the Transjordan—regions directly east and southeast of Jerusalem.

Scripture itself uses the phrase with similar flexibility. The “people of the east” include Arabian groups; wisdom is said to come from the east; and wealth flows westward along established caravan routes. Matthew’s language fits squarely within this biblical worldview. He does not name an empire, nor does he emphasize distance. His concern is direction and origin: these are Gentiles arriving from Israel’s eastern horizon, responding to a sign God has placed in the heavens.

The phrase “we saw His star in the east” further supports this reading. The star is not a navigational device but a sign that initiates inquiry, study, and preparation. The Magi observe it in their homeland, discern its significance, and only then undertake their journey.

Prophetic Expectation: Isaiah 60 and Psalm 72

Matthew’s account resonates deeply with Israel’s prophetic imagination, particularly Isaiah 60 and Psalm 72. Isaiah envisions the nations streaming to Zion when the glory of the LORD rises upon her:

“The multitude of camels shall cover thee… they shall bring gold and incense; and they shall shew forth the praises of the LORD.”

The regions named—Midian, Ephah, Sheba—are Arabian lands, renowned for caravan trade and incense. The imagery presupposes established trade networks and Gentile participants who recognize that God has acted decisively for Israel.

Psalm 72 frames the same hope in royal terms:

“The kings of Sheba and Seba shall offer gifts.”

Though Matthew does not call the Magi kings, their actions align perfectly with this expectation. They bring tribute appropriate to a king, drawn from the wealth of their land, acknowledging a reign they have not yet seen but already believe to be real. Their homage is political, economic, and theological all at once.

Herod’s Fear and Jerusalem’s Unease

When these men arrive in Jerusalem asking, “Where is He that is born King of the Jews?” the reaction is immediate and telling. Herod is troubled, and all Jerusalem with him. This is not the response to idle speculation or foreign superstition. It is the response to a credible, politically charged inquiry.

From Herod’s perspective, the danger is acute. Nabataean dignitaries—representatives of a neighboring kingdom with historical ties to Edom—are publicly affirming the birth of a legitimate Jewish king. They bypass Herod entirely, appealing instead to prophecy and divine revelation. Their question implicitly denies Herod’s claim and exposes the insecurity of his rule.

That Herod responds with deceit and violence rather than investigation reveals how deeply the inquiry strikes. The Magi do not threaten with armies, but with recognition—and recognition is enough.

Time, Distance, and Deliberate Obedience

Matthew’s account allows for a significant interval between the appearance of the star and the Magi’s arrival in Bethlehem. Herod’s order to kill children two years old and under suggests a measured attempt to eliminate a threat whose timing he could not precisely determine. This gap is not a problem but a clue.

A Nabataean journey would not have been impulsive. Observation, consultation, preparation, and the organization of a diplomatic caravan would take time. Once underway, the journey itself—from Petra or the Transjordan to Judea—could be completed in a matter of weeks, not months or years. The Magi’s obedience is marked by patience, cost, and resolve.

Conclusion: The East Recognizes Its King

Seen through this lens, the Magi are neither romantic figures nor theological abstractions. They are historical actors—Gentile elites from the east, shaped by trade, wisdom, and prophecy—who recognize what Jerusalem’s leaders do not. They come not to seize power, but to honor it; not to debate Scripture, but to respond to revelation.

In Bethlehem, Isaiah’s vision begins to take flesh. Gold and incense are laid before a child. Psalm 72’s hope finds its first fulfillment. The nations do not yet stream in multitudes, but they come in earnest, bearing costly gifts and humble worship.

The tragedy, as Matthew presents it, is not that Gentiles arrive late, but that Israel’s king is first welcomed by those from the east—while the throne in Jerusalem trembles, and the city remains silent.